The tragedy of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s has always been a story told in reverse. By the time the diagnosis arrives—prompted by a forgotten name, a trembling hand—the disease has already been silently laying siege to the brain for years, even decades. The damage is already done.

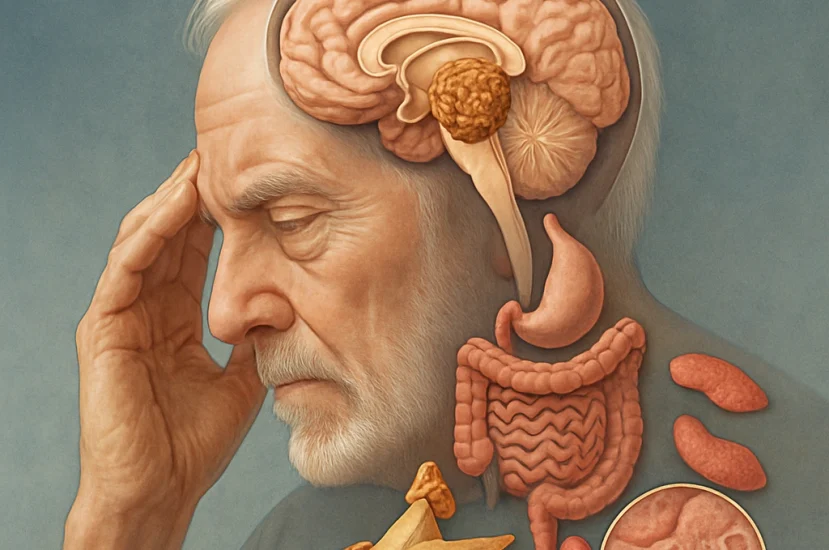

But what if the first chapter of that story wasn’t written in the brain at all, but in the gut, in the blood, in the subtle dysfunctions of the body’s metabolism, decades earlier? A sweeping new study, published in Science Advances, is offering the most compelling evidence yet that the earliest clues to these devastating neurological diseases are not subtle at all. They are the common, treatable, and often ignored ailments of mid-life.

The Body’s Breadcrumbs

The research challenges the long-held view of these as isolated brain disorders. Instead, it paints a picture of a systemic breakdown, a body-wide process where the brain is simply the last domino to fall. After mapping the health histories of thousands of individuals, scientists found a web of connections between more than 150 common health conditions and a future diagnosis of neurodegeneration.

The same culprits appeared again and again. Both type 1 and type 2 diabetes were strongly linked to a higher risk for both Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. So were imbalances in thyroid hormones, deficiencies in vitamins D and B, and a whole host of gastrointestinal problems, from chronic indigestion to irritable bowel syndrome.

“What’s striking is how clearly systemic disorders, especially those related to the gut-brain axis, connect to neurodegeneration years before diagnosis,” said Dr. David Perlmutter, a neurologist who reviewed the findings. “It reinforces the idea that these conditions are the end result of a process that has been unfolding silently for years.”

A Conversation Between Gut and Brain

The gut-brain axis—a constant, two-way superhighway of communication between our digestive system and our brain—has become a focal point of this new understanding. Disruptions in the gut can send inflammatory signals or disruptive hormonal messages straight to the brain.

This may explain why issues like chronic gastritis, intestinal infections, and inflammation in the esophagus so often showed up in patient records years before a neurological diagnosis was ever made.

“It signals a profound shift in thinking,” notes Dr. Lucy McCann, a physician and nutritionist. “Brain health isn’t just dictated by genetics. Nutrition, metabolism, and the gut’s conversation with the brain are major players.”

The Crucial Element of Time

Perhaps the study’s most powerful contribution is its focus on when these other health problems appeared. The researchers found that the earlier a condition was diagnosed, the stronger its predictive power.

For Alzheimer’s, a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes carried the greatest risk when it occurred 10 to 15 years prior to the first signs of dementia, suggesting a long, slow burn of metabolic damage. For Parkinson’s, type 1 diabetes was most predictive when diagnosed five to ten years before the onset of motor symptoms. It’s a chilling reminder that the health choices of mid-life can cast a very long shadow.

Of course, these connections don’t yet prove that a gut ailment causes Alzheimer’s. It may be that both are symptoms of a deeper, underlying problem, like chronic inflammation. But that doesn’t diminish the opportunity this new knowledge presents.

It points toward a future where a doctor could look at a patient’s metabolic panel, their vitamin levels, and their digestive health not just to manage their current condition, but as a window into their future neurological risk. It suggests we’ve been looking for the beginning of the story in the final chapter. The real prologue, it turns out, may have been happening all along, not in the brain’s silent decline, but in the body’s loudest cries for help.